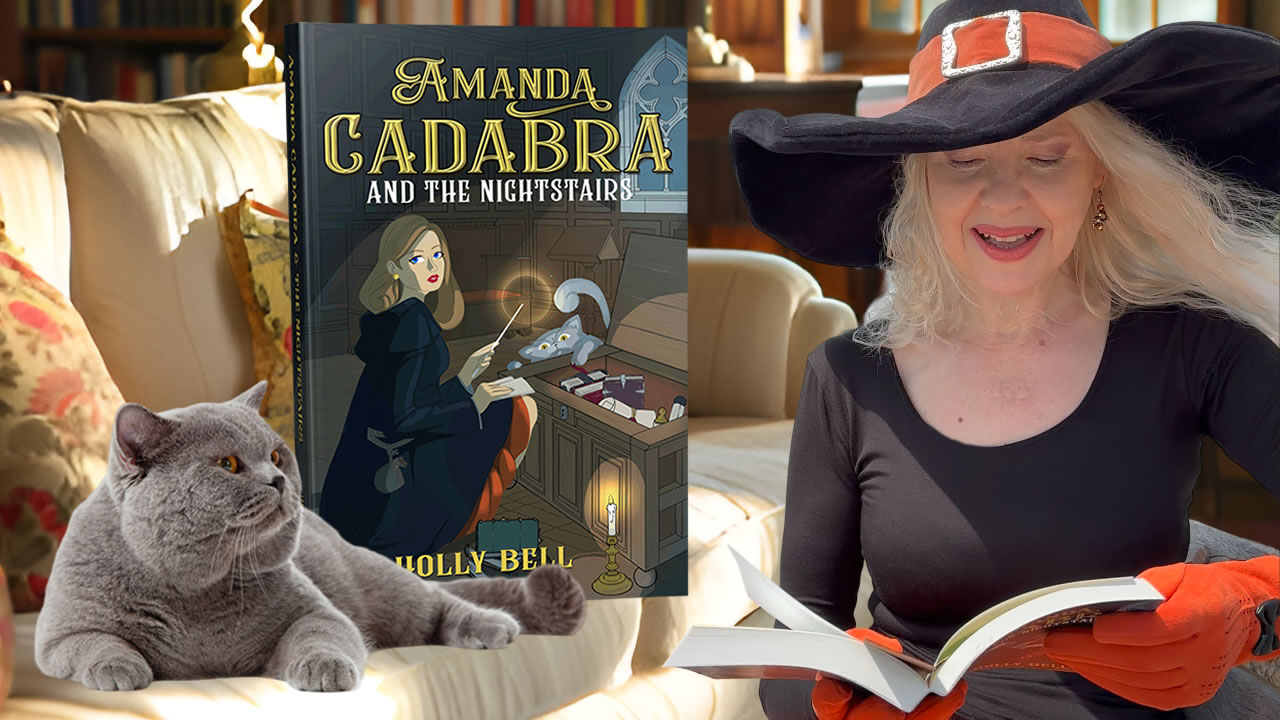

TRAILER BOOK 8 - AMANDA CADABRA AND THE Nightstairs

Chapter 01

It was a blissfully sunny August Sunday, and, as the villagers expected, Amanda Cadabra and her irascible feline companion were making their way towards their favourite picnic spot. Jonathan, the dazzlingly handsome but incurably shy assistant librarian, had raised a hand in greeting as they’d passed.

Amanda Cadabra and The Nightstairs

Chapter 01

It was a blissfully sunny August Sunday, and, as the villagers expected, Amanda Cadabra and her irascible feline companion were making their way towards their favourite picnic spot. Jonathan, the dazzlingly handsome but incurably shy assistant librarian, had raised a hand in greeting as they’d passed.

Latest Sequel

Available on Kindle. Buy Your Copy Today!

Four strangers, one missing dog and a body. But Sunken Madley is just a quaint, peaceful English village. What does the 1000-year-old ruined priory have to do with it? The answer, as it so often does, lies in the past.